I attended a webinar on the "Bicyclists’ Injuries and the Cycling Environment" (BICE) study back in January. The BICE study examined which route types are associated with higher and lower cycling injury rates. The webinar covered a summary of their study's results, which will be available soon online. While some of the study concepts may difficult to understand without an academic research background I thought it was interesting to convey how this study approached the difficult area of injuries and cyclists from a new angle. And from their study we find some interesting results, the most interesting being that they have shown that cycle tracks and local streets that restrict through motor traffic are the two types of routes that reduce the risk of injury for cyclists compared to the typical arterial road with parked cars (exemplified by streets like Dundas, Queen, Bloor and so on).

The innovative BICE study, led by M Anne Harris, was designed with case-crossover design features. In their view, using a case-crossover design is a more reliable way to set up such a study since there are so many variables involved and it would be quite difficult to control for them otherwise. Previous studies faced difficulties in assessing denominators for risk calculations and controlling for confounding variables (variables that correlated with both the dependent and independent variables). The researchers hoped "that the value of this method and the efficiency of the recruitment process will encourage replication in other locations, to expand the range of cycling infrastructure compared and to facilitate evidence-based cycling infrastructure choices that can make cycling safer and more appealing."

Crossover studies according to Wikipedia:

A crossover study has two advantages over a non-crossover longitudinal study. First, the influence of confounding covariates is reduced because each crossover patient serves as his or her own control. In a non-crossover study, even randomized, it is often the case that different treatment-groups are found to be unbalanced on some covariates. In a controlled, randomized crossover designs, such imbalances are implausible (unless covariates were to change systematically during the study).

Second, optimal crossover designs are statistically efficient and so require fewer subjects than do non-crossover designs (even other repeated measures designs).

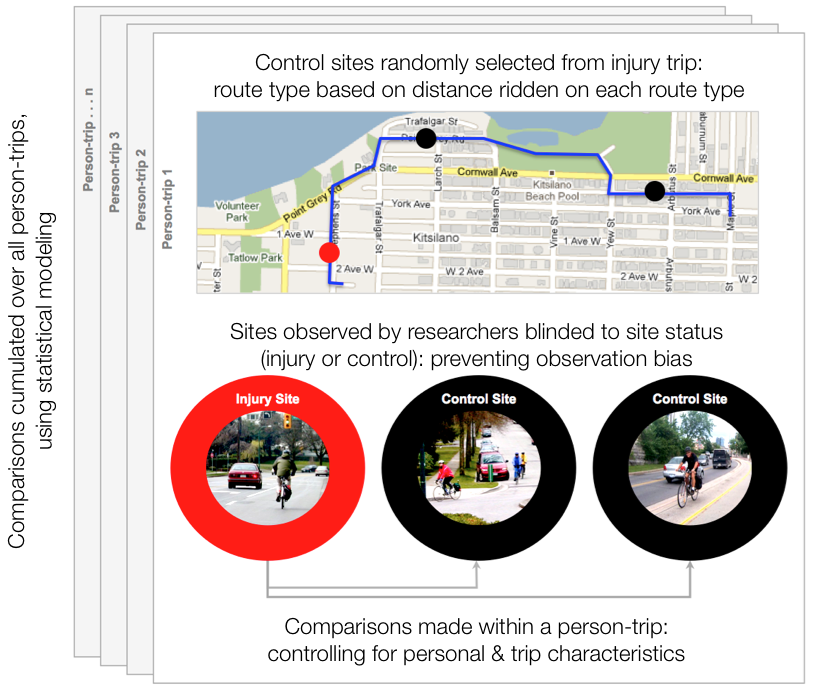

In their crossover study design they interviewed the participants and took control sites randomly selected from the injury trip. The route type was based on distance ridden on each trip. The sites were then observed by researchers who were blind to the status of the site - whether it was an injury site or control. This prevented observational bias. The crossover design meant that comparisons were made within a person-trip, thus controlling for personal and trip characteristics. Then using statistical modelling they accumulated the comparisons over all the person trips.

Injured cyclists were recruited from the emergency departments of five hospitals in Vancouver and Toronto, Canada. In 18 months, 690 participants were successfully recruited and interviewed. Each participant was interviewed to map the route of their injury trip, identify the injury site and select two control sites at random from the same route. Infrastructural characteristics at each study site were scored by site observers who were blinded as to whether sites were crash or comparison sites. Analyses will compare infrastructural variables between case and control sites with conditional logistic regression.

They found that the typical cyclist profile in the study cycled more than 52 times per year (88%) which might be explained that the more trips one takes the greater the exposure to potential injury. Most wore helmets (59% in Toronto and 76% in Vancouver). I found the Vancouver number surprisingly low considering that there is a helmet law. Could it be that not only do helmet laws discourage some from cycling but that they aren't even all that effective in raising the helmet wearing rates compared to other methods?

Of the injuries investigated (% of 690), 22% involved a motor vehicle, 10% involved a vehicle door, 14% involved streetcar track (and 6% involved both a streetcar track and a motor vehicle where a cyclist avoided a motor vehicle and fell because of streetcar tracks), and 5% involved a cyclist avoiding a collision with a motor vehicle.

The study used 15 route types and compared them. They included more route types and built-environment factors than other similar studies, by also looking at surfaces, intersection type, categorizing streets into minor/major, with/without bike facilities and categorizing off-road into bike paths, cycle tracks and sidewalks.

For the purposes of comparison they presented their statistical analysis as the relative risk of injury as compared to their reference route category, a major street with parked cars and no bike infrastructure such as we see on Bloor Street. The reference category equalled 1 and their other route types either had a fraction of that risk or a multiple.

They found that:

- All other route categories were lower risk than their reference route type.

- Cycle track (physically separated bike lanes from traffic) was 1/10 the risk of reference category. This was statistically significant.

- The reference category with bike lanes didn't provide statistically significant less risk.

- a bike lane on major street with no parked cars was found to be statistically significant at 1/2 the risk. This may indicate that removing parked cars has a bigger impact than adding a bike lane.

- A local street with or without bike infrastructure had the same risk factor has bike lanes on major streets with a statistically significant risk of 1/2 that of the reference category.

For the routes fully separated from traffic, they found that:

- sidewalks had a statistically insignificant and small drop in risk. This is bound to be controversial given that previous studies have found increased risk, though in the case of the well-known study by Wachtel and Lewiston (1994) they found that riding on the sidewalk in the same direction of traffic had almost the same risk but that riding against the flow of traffic on the sidewalk carried 4 times the risk.

- likewise multiuse paths, whether paved or unpaved, provided only a slight, stastically insignificant drop in risk.

They also looked at non-route features. Of some of the other features studied but were not statistically significant, included intersections with a slightly higher risk and bike signage which provided a slightly lower risk.

The features which did show a statistically significant increased risk, included downhill grade at 2 times the risk of the reference category, routes with streetcar tracks at 3 times the risk, and construction on a route at 2 times the risk. As well they found that uncontrolled intersections were 3 times more risky and the traditional traffic circle (unlike the roundabout) were 8 times more risky. The risk of injury was 10 times for cyclists travelling opposite to motor vehicle traffic (though I'd like to see this broken down into arterial and local streets).

The researchers also looked at risk in relation to cyclist traffic counts. They found that at least at intersections, that an increased number of cyclists actually also increased risk. This runs counter to the safety in numbers research by Dr. Jacobsen, which looked at the correlation on a country-wide scale. What isn't true on any individual intersection may still be true when looking at the cycling rates across a city or country.

They also found that motor vehicle speed affected the risk of injury by cyclists, where motor vehicle speed was less than 30km/h this provided a statistically significant decreased risk.

Preferences

It's important to not just study the safety issues but also the preference by most cyclists. This is because cyclists will still take the routes they prefer over those which are deemed "safe". And also because in study after study it has been shown that the health benefits (physical exercise, less pollution) far outweigh the health costs (in terms of injuries and fatalities). A general policy could arguably be to build route types that best match up lower risk with preferences.

Most cyclists prefer bike paths, multi-use paths, local streets, and cycle tracks. Preference and safety match fairly well. By choose the route types that match both safety and preference would be cycle tracks, local street with motor traffic diverters (to discourage through traffic), and bike only paths.

There were some limitations to the study:

- most severe and mildest injuries were not included

- 20 people couldn't be included because their injuries were too severe and they couldn't actively participate

- the mildest injuries weren't studied since only hospital admittances were focused on

- the researchers couldn't study different cycle track designs so a comparison could be made between, say, unidirectional and bidirectional cycle tracks

- there were not enough innovative intersection designs to study

When their study summary is posted online I will update this post with a link or pdf.

Comments

W. K. Lis

Local streets would be fine

Mon, 02/27/2012 - 17:38Local streets would be fine except that in the suburbs they are mostly cul-de-sacs that do not go in the same direction as the main arterial roads. In the more urban areas, they are also not continuous, causing riders to jig-jag to get to their destination. Bike paths are useless as they mostly are in river valleys or away from the rider's destination.

Random cyclist (not verified)

FEWER! FEWER Injuries. Don't

Mon, 02/27/2012 - 21:43FEWER! FEWER Injuries. Don't you people have a proofreader?!

herb

No, "we people" don't have a

Thu, 03/01/2012 - 08:53No, "we people" don't have a proofreader. That's where you come in.

Title corrected.

the Random cycl... (not verified)

A proof reader is not in

Thu, 03/01/2012 - 21:54A proof reader is not in budget of zero dollars

Yeah that's usually a pet peeve of mine too, but still a distant second to people referring to crashes as "accidents."

Just keep in mind that I bike to is a a labour of love run from our living room. Herb is up all all hours gathering information and writing these blog post. As his most fierce critic, I don't get to be the proof reader - well that and I went on a work to rule campaign after being the blog widow. But I'd say for small-town a farm boy, raised learning two languages, for the most part he does quite well writing on urban cycling issues for the rest of us.

Bethany

Wow, there was a lot of work

Thu, 03/01/2012 - 10:32Wow, there was a lot of work that went into this study. It sounds like there could be some real positive change on the way for these cyclists. Hopefully one day injuries between cyclists and cars will be a thing of the past.

Cyclists are hurt by vehicle drivers all the time because of the a budget limit for safety so it is important for drivers to learn that they do in fact have to share the road.

Karl (not verified)

The cul-de-sacs in the 'burbs

Mon, 03/05/2012 - 22:15The cul-de-sacs in the 'burbs just need to have connections added if there's any room to do them in. It depends on how it was designed. Some have a walkway between yards. That just needs to be made to be shared biking/walking.

In other places there isn't any place. I wonder if a city could buy strips from two residents and make one.

Trisha (not verified)

I think that bad parking

Wed, 03/21/2012 - 13:32I think that bad parking habits are what is very, very dangerous for bikers. My daughter was hurt several months ago just because there was a track in the bike lane! Meanwhile, parking a car in Toronto is considered to be easy on average (especially when compared to the other big cities of the world), there is a desperate situation for bikers in general. I hope competent persons will soon notice the alarming situation and adopt required legislation.