Me biking in snow and cold. That's actually near Penetanguishene, a place where this is actually considered a light sprinkling. We thought it was going to be still fall but—surprise!—it snowed.

Tom Babin's new book Frostbike—The Joy, Pain and Numbness of Winter Cycling—arrived just in time to help me prepare for this year's cold, snow and wind. Frostbike is a book about Tom exploring the history cycling in winter, how cities with strong cycling cultures deal with winter, and how he himself, as a suburban Calgarian, evolved his own thinking and behaviour around taking a bike to work. Tom shows us that cycling in winter is not complicated and that the cold and snow is not a problem. The biggest barrier to good winter cycling are the cultural barriers and lack of good cycling infrastructure found in North America compared to Europe.

Both my wife and I cycle all winter, except for the crappiest of days. The difference between us is that my wife has to get to her workplace everyday whereas I have the privilege of staying at home in my sweatpants if I don't feel like hoofing it over to the CSI office. So it's much more critical that my wife has a good commute than I have one. For instance, just last winter I outfitted her bike with a front brake so that she'll have more control.

Mind you, I still bike way more than the average since we don't have a car and taking transit is just boring and exasperating. We do our shopping, errands, visits and so on all by bike. So we both know full well how to dress for the ride. Clue: just dress warmly, especially the hands, and if you think you're going to sweat then dress more lightly because you want the body heat and sweat to escape.

But, we're nothing special. You don't have to be an athlete or superhero to bike in the winter. In cities where Tom visits in his book, such as in Finland and Denmark, everyone from young to old bikes in the winter. Even here in Toronto, where many people put their bikes away at the first nip in the air, I see everyone from young hipsters on their ironic ten-speeds to elderly Chinese-Canadians biking on the sidewalk in the winter. The decision to bike in winter seems to be just as much a function of habit and culture as anything.

Did you know the world's best winter cycling city is Oulu, Finland? I didn't until Tom explained how he stumbled upon this fantasy city at Velo-City, Vancouver 2012 when he ends up at the least popular seminar there: winter cycling where people get into heated discussions about salt. But when a visiting Finn describes Oulu, it seems to be from a different world.

Tom gets a bit obsessed with seeing Oulu and travels for the first Winter Cycling Conference to get a first-hand look at what first-rate winter cycling cities look like. (This year's Winter Cycling Conference was actually in Winnipeg). From the way Tom describes it, Oulu is like heaven for the bundled up cyclist. They have well-maintained trails but they don't plow them per se. They groom them like a ski trail. Instead of copious amounts of salt, their trails all have a nice layer of packed snow that is surprisingly easy to bike on and isn't slippery at all.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbStrnNvq5E

"The Winter Cycling Capital of the World"

As much as I don't like thinking about having to go through winter, once I'm in it, I, like Tom learned while writing his book, appreciate being outside in the fresh air. We spend too much winter indoors. Being in an urban environment doesn't always help, but my wife and I like to be a bit active: skating and skiing. In the book, Tom describes how he made a conscious effort to enjoy winter more:

No more would I suffer through winter and revel in the outsider status it gave me. My mission was to romp through it, and in my sheer joy would change my own attitudes and convert those around me into winter believers.

Like all experiments, he has mixed results (partly thwarted by southern Alberta's warm Chinook winds) but the idea is sound.

But with substandard urban infrastructure it's difficult to enjoy some activities. Skating rinks are crowded and have limited hours; there are very few continuous trails that we can use for skiing in the city; and the City doesn't plow or groom the vast majority of the park trails and bike lanes.

Calgary, interestingly, actually plows most of its trails. The story behind it is equally interesting as Tom relates. Calgary trail plowing was a DIY/protest plowing by a bunch of volunteers using at first their own bikes outfitted with makeshift plows and later with their own truck. Eventually the truck broke down and the citizenry, which had become quite used to the nicely plowed trails, started complaining in large numbers to politicians and City staff. The volunteers in essence forced the City's hand.

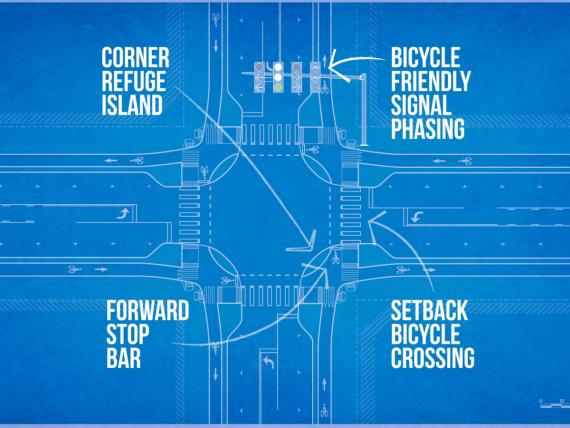

But Toronto staff is working hard on improving things here. Christina Bouchard of Toronto's cycling unit presented at the Winnipeg winter cycling conference on creating a "snow cycling network".

To plough the entire on-street cycling network would cost an estimated 3 Million CAD, but the plan developed will only cost $650,000. This is because the Transportation Services Department was able to prioritize the most-used cycling routes. Using data from spot and cordon counts, the city identified the routes with an excess of 2,000 cyclists in a 24-hour period during the summer.

But Calgary's example is still a good lesson for Toronto cyclists who want to keep prodding the City to start plowing more of the trails. Plow it and they will come.

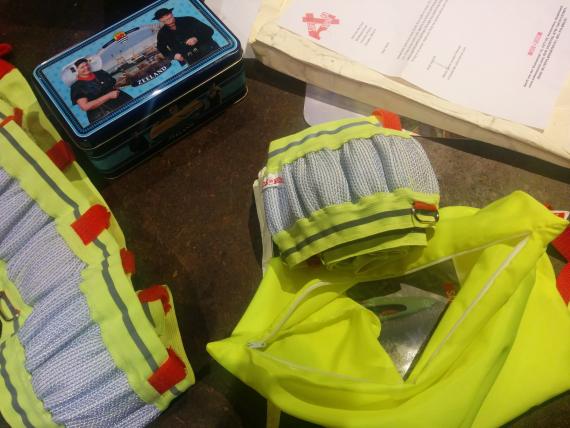

Good for you, Tom, for helping me get over the dread of an upcoming winter on bike and back into the rhythm of dressing up for the weather. Mind you, the ice will still be an issue, but for that my wife and I will be soon reviewing this product I came across, the "Sneeuwsok" (a grippy snow sock for your tire). Here's what it looks like fresh form Hollandland (Zeeland snoepje kas—candy box—not included):

It only works on bikes with no rim brakes so my wife will be trying it out on her Dutch bike with rollerbrakes. I haven't tried out studded tires which probably work even better on ice but I hear they work poorly on dry pavement. The MEC site suggests adjusting the air pressure depending on the road conditions. Perhaps someone who's tried them out can let us know.

But still no snow sticking around. Snow already dammit! Snow!